After a huge Chinese rocket plummeted apparently into the ocean late Saturday (May 8), NASA's new administrator condemned the country's use of launch technology that makes uncontrolled reentries from orbit.

The rocket body that captured headlines around the world for more than a week was used during the April 28 launch of Tianhe, the core module of a new space station China is constructing in orbit. The launch was only the second for the nation's new Long March 5B; the vehicle's first launch, on May 5, 2020, also resulted in an uncontrolled reentry, this time raining pieces down in inhabited villages in Côte d'Ivoire, according to reports at the time, luckily with no casualties.

The rocket's first launch lofted an uncrewed test flight of the vehicle that astronauts will ride into orbit in conjunction with the new space station's construction. China plans two more Long March 5B launches in 2022 for experiment modules to join Tianhe, according to Space News; crew and cargo launches associated with the station appear poised to use other rockets in the Long March family. It is unclear whether China plans any modifications in these future launches to avoid space debris.

Related: China's huge rocket falling from space highlights orbital debris problem

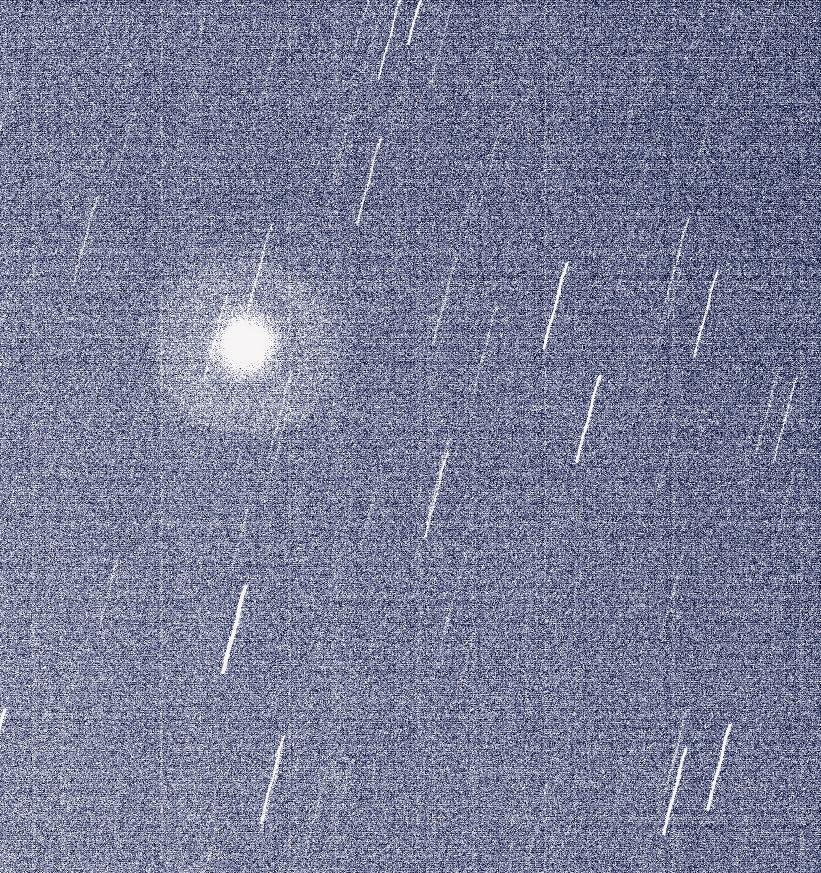

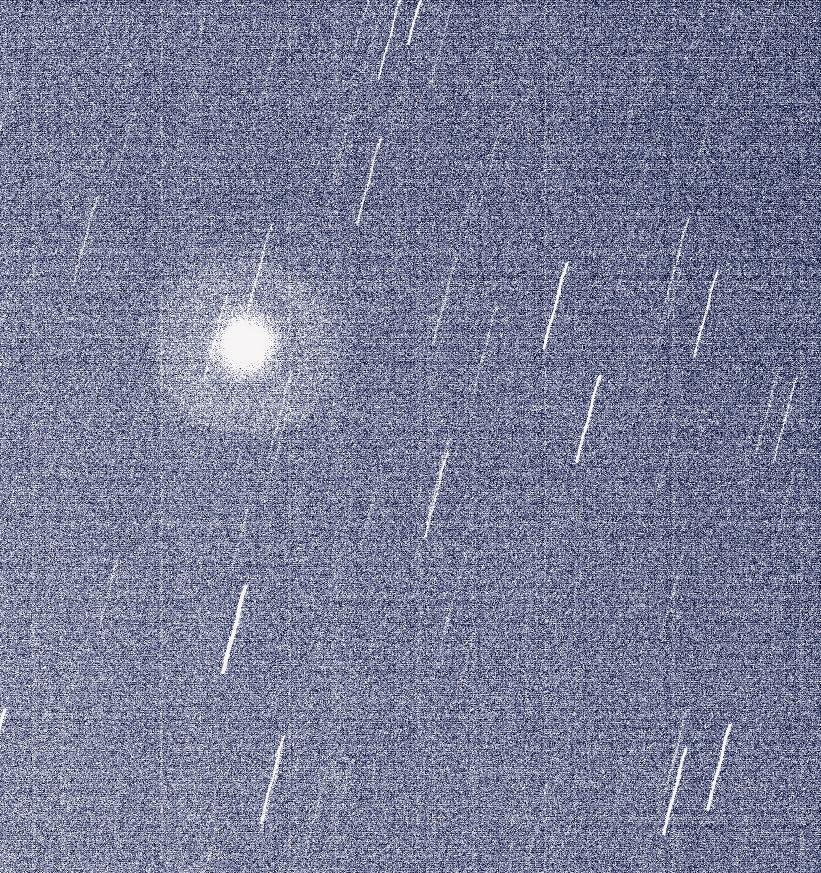

NASA Administrator Bill Nelson, just days into his leadership of the agency, released a statement Saturday (May 8) after the U.S. Space Command's 18th Space Control Squadron confirmed the Chinese Long March 5B core stage re-entered the atmosphere at 10:14 p.m. EDT (0214 GMT) and fell into the Indian Ocean north of the Maldives.

"Spacefaring nations must minimize the risks to people and property on Earth of re-entries of space objects and maximize transparency regarding those operations," Nelson said in a statement posted on NASA's website. "It is clear that China is failing to meet responsible standards regarding their space debris."

The China Manned Engineering Office confirmed what the U.S. military posted, according to Al-Jazeera. "The last-stage wreckage of the Long March 5B Yao-2 launch vehicle has reentered the atmosphere" and most pieces had burned up, the statement noted. Chinese officials said earlier this week that the risk posed to Earth's population by the 23-ton (21-metric ton) core stage was low.

As of early Monday (May 10), the White House had not released a statement about the Chinese incident, although earlier in the week, said it was closely monitoring what would happen and encouraged China to follow international standards in space debris. U.S. Space Command's first statement about the core stage fall noted the entity "does not conduct direct notifications to individual governments."

Congress banned NASA from making bilateral agreements or cooperating with China in April 2011, and the agencies have had limited official contact in the decade since, although collaborations still happen. For example, NASA collaborated with China to use the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter to monitor the Chang'e-4 lander and Yutu 2 rover that alighted on the far side of the moon in January 2019.

At the time, NASA (which said it had certified its work with Congress) told Scientific American the prohibition did not apply to LRO tracking. Further, the agency said that the activity did not "pose a risk of resulting in the transfer of technology, data or other information with national security or economic security implications to China," and that the relevant Chinese space authorities NASA is interacting with "do not involve knowing interactions with officials who have been determined by the U.S. to have direct involvement with violations of human rights."

If property damage or casualties occurred due to the rocket body's fall, China is technically responsible under the liability convention of the 1967 United Nations' Outer Space Treaty. That said, one country has successfully gained compensation from this international agreement — Canada, which dealt with radiation in its north following the fall of Soviet nuclear satellite Kosmos 954 in 1977.

Space debris expert Jonathan McDowell, an astrophysicist at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, told Space.com on Friday (May 7) that the sheer size of China's rocket made this a larger piece of uncontrolled debris to deal with than we've seen in several decades, since the community has adopted more stringent policies about launch debris.

The international standard, he said, is not to allow huge rockets to achieve orbit, instead cutting off their engines a little early to force them back into Earth in a predictable location. Any payload requiring orbital operations are boosted through another smaller stage.

"It is critical that China and all spacefaring nations and commercial entities act responsibly and transparently in space to ensure the safety, stability, security and long-term sustainability of outer space activities," Nelson wrote in the NASA statement.

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.