Early in the coronavirus pandemic, I asked a simple question. Could Sweden’s laissez-faire approach to the coronavirus actually work?

Unlike its European neighbors and virtually all US states, the Swedes had opted to not shut down the economy. The country of 10 million people took what was at first described as “a lighter touch.”

While other countries closed schools and businesses, life in Sweden stayed pretty normal. Kids went to public pools and libraries, while adults sipped wine and had lunch in local bistros. Though mass gatherings were prohibited, children kept going to school, though students older than 16 were encouraged to attend classes remotely. The Swedish government also encouraged people to work remotely and asked people over 70 to isolate themselves, if possible.

For taking this approach, Sweden—and the architect of its public health policies, Anders Tegnell—was widely condemned. Consider just a sampling of headlines:

“The Inside Story of How Sweden Botched Its Coronavirus Response”

Foreign Policy, Dec. 22, 2020

“Sweden Stayed Open And More People Died Of Covid-19, But The Real Reason May Be Something Darker”

Forbes, July 7, 2020

“Sweden’s Covid-19 strategy has caused an ‘amplification of the epidemic”

France 24, May 17, 2020

“Sweden’s Unconventional Approach to Covid-19: What went wrong”

Chicago Policy Review, Dec. 14, 2021

“Sweden Has Become the World's Cautionary Tale”

The New York Times, July 7, 2020

These are just a few examples of the avalanche of criticism Sweden received for not locking down its economy like other governments around the world. A quick Google search will turn up dozens more.

I spent a great deal of time in 2020 and 2021 arguing that the media was getting the narrative wrong on Sweden, pointing out that Sweden’s response had resulted in exponentially fewer deaths than modelers had predicted and lower mortality overall than most of Europe.

The BBC also noted Sweden’s economy had not suffered nearly as much as the economies of other European nations, and, more importantly, as other countries were implementing more lockdown measures in 2021, daily COVID deaths in Sweden had reached zero.

While many nations are gearing up for more lockdowns, daily deaths in Sweden are still at 0.This isn't what they said would happen. pic.twitter.com/udOcaacwx4

— Jon Miltimore (@miltimore79) July 22, 2021That was nearly 9 months ago, however. How does Sweden rank compared to other European countries today?

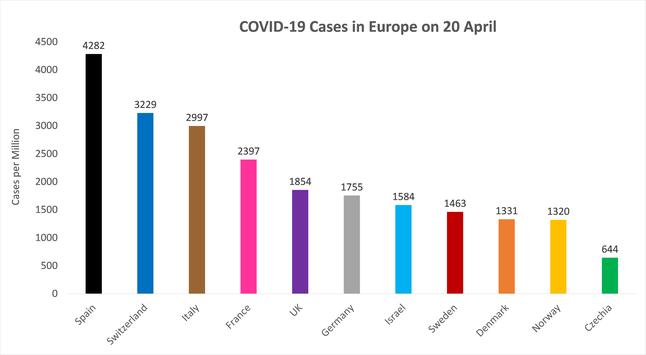

Like many countries, Sweden saw cases spike with the arrival of Omicron, which resulted in a new wave of COVID deaths. However, the wave was much smaller than in other countries. In fact, Sweden’s overall COVID-19 mortality rate throughout the pandemic is one of the lower rates you’ll find in all of Europe.

Remember when everyone mocked Sweden for their COVID strategy? pic.twitter.com/TS8wKBsTfc

— Jon Miltimore (@miltimore79) March 21, 2022The point in sharing this information is not to take a victory lap. The point is to learn from the mistakes made during the pandemic.

In March of 2020, when public health officials realized COVID-19 was more deadly than they previously believed, they panicked. Instead of pursuing similar courses humans had pursued in previous pandemics, public health authorities decided to copy the strategy of China—one of the most totalitarian regimes on the planet—and use the government to force entire sectors of the economy to shutdown. (Americans were told this was just for 15 days to “flatten the curve,” something that was quickly proven to be untrue.)

The strategy failed miserably. Study after study after study has shown the lockdowns failed to adequately protect populations, which is why non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) have been scrapped by countries around the world.

Shutting down society, however, came with serious and deadly consequences. The World Bank reported last year that global poverty surged during the pandemic, with 97 million more people living on less than $1.90 per day. In the United States, 8 million more people fell into poverty in 2020, tens of millions lost jobs, and hundreds of thousands of businesses went under. To mitigate these harms, the government “flooded the system with money,” which has resulted in surging inflation. The losses went beyond financial costs, of course. Cancer screenings plunged and drug overdoses reached record highs, resulting in an untold number of deaths.

And on Tuesday, The New York Times revealed the latest unintended consequence of the government’s lockdown experiment: a new study shows alcohol-related deaths spiked in 2020, increasing 25 percent from the previous year.

“The assumption is that there were lots of people who were in recovery and had reduced access to support that spring and relapsed,” said Aaron White, one the report’s authors and a senior scientific adviser at the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

“The assumption is that there were lots of people who were in recovery and had reduced access to support that spring and relapsed,” said Aaron White, the report’s first author. https://t.co/nBOQ6oLcgP

— NYT Science (@NYTScience) March 23, 2022Public officials made two serious mistakes above all others in their response to the virus. The first was assuming they possessed the knowledge and ability to contain a highly contagious respiratory virus through lockdowns and other NPIs.

Many world-leading epidemiologists at the time, like Tegnell, saw the futility of such an approach.

“In early March 2020, when Italy and Iran started to report many COVID deaths as the first countries outside China, it was clear to any knowledgeable infectious disease epidemiologist that the virus would eventually spread to all parts of the world,” Martin Kulldorff, a biostatistician and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School from 2015 to 2021, told me. “At the time, we only knew a small proportion of the actual cases, so it was clear that it had already spread elsewhere and that it would be futile to try and eliminate the disease with contact tracing and lockdowns.”

The second mistake public officials made was not considering the unintended consequences of their actions. The writer and economist Henry Hazlitt once pointed out this is one of the perennial flaws in policymaking.

“[There’s a] persistent tendency of men to see only the immediate effects of a given policy,” Hazlitt wrote in Economics in One Lesson, “and to neglect to inquire what the long-run effects of that policy will be not only on that special group but on all groups.”

Hazlitt described this as “the fallacy of overlooking secondary consequences.”

Anders Tegnell, the architect of Sweden’s strategy who recently joined the World Health Organization, was one of the only public health officials in the world who acknowledged these secondary consequences, predicting that “the consequences of shutting down the economy [would] far outweigh the benefits.”

Tegnell was right, the data show. And the critics of Sweden’s policy should acknowledge that.