Ilham Tohti is a practical man. When his daughter, Jewher, complained he was working too much and wasn’t spending enough time with her, he simply moved his desk into her room, forcing her, she recalled with playful annoyance, to do her schoolwork on her bed. When Uyghur students of his couldn’t afford to fly from Beijing to their families’ homes in Xinjiang Province and celebrate the end of Ramadan, he invited them into his own home, splurging on enough halal meat for them all. And months before he was sentenced to life in prison by the Chinese government on charges of promoting separatism, he made arrangements for dividing up his assets and enlisted friends to take care of his family. “Daddy has lots of friends all around the world, many of them you’ve never met,” he told Jewher, “but if you tell them what’s happening, they’re going to help you.”

A practical approach has also defined Ilham’s advocacy on behalf of China’s oppressed Muslim Uyghur minority. Prior to his sentencing in September of 2014, Ilham used his platform as a prominent academic at Beijing’s Minzu University to call attention to the systemic persecution of his people, part of the Chinese government’s broad campaign against minority groups that it believes represent a threat to its one-party rule and territorial integrity. His advocacy earned him near-constant surveillance and harassment, despite the fact that it was couched in pragmatic appeals to the government’s interests. He discovered that even straightforward descriptions of the Uyghurs’ plight could land him in trouble. “The environment for Uyghurs to survive and develop socially is extremely dire,” he said in a 2008 interview for the site he founded, Uyghur Online. Shortly thereafter, he was arrested for the first time on separatist charges. Jewher Ilham says she has not heard from him since 2017.

A newly released collection of Ilham’s work, We Uyghurs Have No Say, provides a comprehensive analysis of how Uyghurs came to be a subjugated group within China, as well as strategies for remedying the situation through interethnic dialogue and policy reform. Yaxue Cao, who compiled and translated a bulk of the collection — which includes articles, an essay, statements, and interviews, all written between 2008 and 2014 — said she hoped the work would resonate with western audiences “because here is a Uyghur scholar explaining the root causes. It’s a quick introduction for their understanding of the issue.” The book also raises the question of whether Ilham’s style of dissent can have a future when the Communist Party seems so entirely closed off to reform, and what the Uyghurs and the rest of the world might have to resort to next.

It’s striking that Ilham produced all of this work before the Chinese Communist Party began its most serious crackdown on Uyghurs in 2017: Starting that year, over a million Uyghurs, along with other minorities, were forced into internment camps in Xinjiang. The Chinese government initially denied the existence of these camps, in which Uyghurs are forced to renounce their language and religion and are subjected to routine torture, according to reports. The government now calls them “vocational training centers” and claims they help “people to learn more about the law, to acquire good skills to improve their lives, find good jobs,” per Cui Tiankai, the Chinese ambassador to the United States. An estimated 5 to 10 percent of detainees die each year, and many others are eventually transferred to formal prisons or labor camps. In and around Xinjiang, an autonomous region home to a majority of Uyghurs, the CCP has also employed the use of highly regimented electronic surveillance, including mandatory spyware apps, GPS trackers, and facial-recognition software, to monitor their every move. With further reports of forced labor, forced sterilization, and children being separated from their parents, the U.S. Department of State has determined the Chinese government’s actions constitute genocide.

“Instead of an image, it’s more of a sound,” Jewher, who’s lived in the United States since 2013 and Washington, D.C., since 2019, said of how she remembers her father. “The sound of his typing. Sometimes for over ten hours.” He published the bulk of that work on Uyghur Online, a website he founded in 2006 to promote discourse between Chinese minorities and those who identify as Han, China’s majority ethnic group. Ilham and other writers published articles on cultural, political, and socioeconomic trends among Uyghurs and other minorities while repeatedly (and carefully) petitioning for fair treatment. In addition, the forums, which Ilham monitored and contributed to extensively, provided a platform for Uyghurs, Kazaks, and Kirghiz to engage with Hans as equals — and, Ilham hoped, to relate to one another.

“He knew nearly every single contributor on the site by their username, including their viewpoints and most recent comments,” wrote Ilham’s longtime friend and fellow academic, Huang Zhangjin, in an essay published shortly after Ilham was sentenced. Ilham treated Uyghur Online “as if it were his own son.”

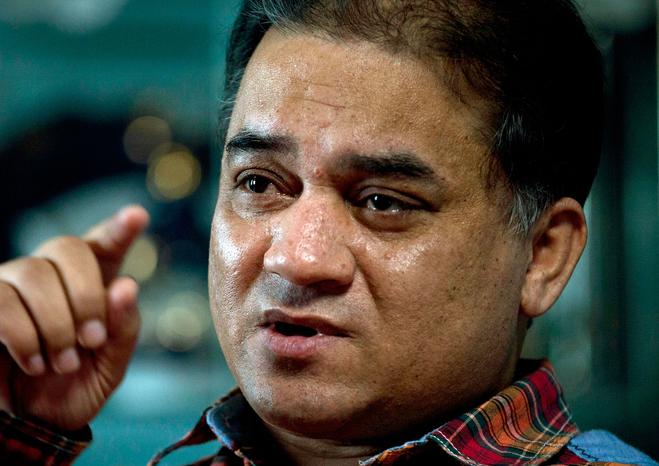

Ilham teaching students at Beijing’s Minzu University.Photo: Federic J. Brown/AFP via Getty ImagesWhen discussing Uyghur persecution with the press, Ilham’s fervor was tempered, if no less intense. “I don’t think the Chinese government’s crackdown will make Uyghurs give up their religion, but it will face more resistance,” he told the Financial Times in July of 2013, just three months before a group of alleged Muslim extremists plowed a car through a crowd of people in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square. A month later, another car, this time operated by Chinese officials, drove Ilham off the side of the road in Beijing. The drivers said they “wanted to nong si him,” recalled prominent Chinese dissident Hu Jia in an interview with ChinaFile. “Nong si means kill your entire family.”

In spite of the threats, the maddening surveillance, the government shutdowns of Uyghur Online, Ilham retained his optimism. “I am convinced that China will become better and that the constitutional rights of the Uyghur people will, one day, be honored,” he wrote in a statement released by his lawyer upon receiving his life sentence.

“He was a vanguard of giving constructive criticism on the party’s policy for Uyghurs,” Rian Thum, a historian of Islam in China who wrote a preface for the collection, told me. “He put out a case for a change in policy that included better treatment for the Uyghurs, without questioning any of the pillars of party ideology.” Ilham’s work was of a different stripe than, say, Charter 08, a manifesto co-authored by the Nobel Peace Prize laureate Liu Xiaobo that called for the end of one-party rule.

Rather than encourage a complete overhaul of Chinese government, Ilham warned that the Communist Party’s Uyghur policy would jeopardize its cherished goal of social stability. In an essay at the heart of the book, he addresses the various issues plaguing Uyghurs, including unemployment due to discrimination, the phasing out of Uyghur culture, and segregation within Xinjiang. By oppressing Uyghurs, he writes, the CCP was only encouraging dissent: “If the government is to win broad-based popular support and achieve genuine long-term peace and stability, it must promote further systemic and social adjustments.”

Above all else, Ilham demanded the ethnic autonomy that had been promised to Uyghurs by Chinese law since the 1980s. In addition to establishing Xinjiang as a Uyghur Autonomous Region and Uyghurs as an autonomous ethnic group, the laws also ensure the right for ethnic minorities to develop their own spoken and written language, hold key positions in local government, and have religious freedom. After delineating the CCP’s promises to Uyghurs in one of his articles featured in the book, Ilham pointedly asks, “Have these laws and policies really been implemented in Xinjiang?”

Far from promoting insurrectionary violence or the establishment of a new constitution, his work can seem deferential, though, as Thum pointed out, “To make the kind of direct request for a change in policy, no matter how in the system you are, asking for a change of policy at that level is now seen as a kind of treachery. In the Chinese context, he’s always looked vociferous.”

At times, his writing reads more like one friend’s sober advice to another, possessing a “for your own good” quality while still bearing the mark of lived experience. “Uyghur blood flows in my veins, and I grew up in the embrace of a Uyghur family,” he wrote on the fourth anniversary of “the July 5 incident,” a series of Uyghur protests in Xinjiang’s capital, Ürümqi, which devolved into riots and took the lives of 192 people. “I carry an unavoidable responsibility to both my people and to my country for the correct handling of ethnic relations.”

Following his imprisonment, Jewher Ilham has inherited her father’s mission. As part of her efforts to keep advocating for her father and Uyghurs in general, she has testified before U.S. Congress and met various government officials. Like many Uyghurs living abroad, she can’t communicate directly with her relatives in China, even those who aren’t imprisoned: “[My family and I] have cut our communication completely since 2015,” Jewher told me. “I can’t communicate with my stepmom directly because picking up a phone call from overseas is considered a crime now.” The family relies on Han Chinese friends to relay information to one another. “We would have friends go visit them in person and then record a voice message and then send it to me through that person’s secret phone or something,” she said. “That’s how we talk.”

Jewher said that people would often refer to her and her father as being “copy-paste” versions of each other. She told me about late-night joyrides where they’d blast music by the Turkish singer Tarkan and Ilham’s favorite, “Hotel California.” “People would think it’s like two reckless kids, but they’d turn and see a teenager and her dad,” she laughed. Zhangjin wrote of Ilham, “When he grew excited while speaking, he would invariably rise up out of his seat as if he were a teapot whose lid was bursting under the pressure of steam.”

Jewher’s move to the United States was an accident: In February of 2013, she and her father attempted to board a flight from Beijing to Indiana, where Ilham had been offered a yearlong fellowship at Indiana State University as a visiting scholar. Jewher tagged along, planning to travel with her father for a few weeks before eventually returning home to Beijing. At the Beijing airport, however, Ilham was detained by authorities. Jewher, who was 18 at the time, was deemed a non-threat by Chinese authorities and allowed to board the flight. (“They regret it now,” she said.) Despite her protests to stay with her father, Ilham “made me leave,” she said. Shortly afterward, Ilham was placed under house arrest, as he had been several times since starting Uyghur Online, before eventually being arrested for the last time in 2014.

Jewher has accepted four awards from various human-rights groups, including the PEN/Barbara Goldsmith Freedom to Write Award and Sakharov Prize, on behalf of her father since he was imprisoned. Each time, she said, the organization sets an empty chair next to her onstage, an homage to Ilham. “To be honest, I hate it,” she told me. “Because it reminds me of that 14-hour flight from Beijing to America. Sitting next to my dad’s empty chair.”

In addition to the Uyghur genocide, China’s been under scrutiny for similar forms of persecution in Tibet, as well as a crackdown in Hong Kong on behavior that falls under its increasingly broad definition of “dissent.” In response to mounting calls for action, the U.S. has imposed sanctions on several Chinese biotech and surveillance firms, banned imports from Xinjiang, and declared a diplomatic boycott of the 2022 Olympics. On Monday, the Department of State announced it would be imposing visa restrictions on Chinese officials “who are believed to be responsible for, or complicit in, policies or actions aimed at repressing religious and spiritual practitioners, members of ethnic minority groups, dissidents, human rights defenders, journalists, labor organizers, civil society organizers, and peaceful protestors in China and beyond.”

Some have called opposition to China’s treatment of the Uyghurs one of the only remaining bipartisan issues — though the Uyghur genocide has been used by some American politicians to further a long-standing anti-China agenda, which has only intensified amid a wave of anti-Asian xenophobia caused by the pandemic. This despite the fact that being pro-Uyghur and anti-China are sometimes incompatible. In response to legislation aimed at bolstering technological innovation and education, Republicans zeroed in on new visa opportunities in some of the legislation’s fine print — including a provision to exempt Uyghur refugees from annual refugee caps. “As the Biden Administration continues to mass release illegal immigrants across the country, House Democrats’ CONCEDES Act provides a new unlimited green card program for the Chinese Communist Party to exploit. This is America LAST,” House Republican Leader Kevin McCarthy tweeted.

Among the millions detained in the camps, the Uyghur Human Rights Project has identified 435 Uyghur intellectuals, including doctors, poets, journalists, and professors. According to Cao, part of the driving force behind publishing Ilham’s work was the belief that his words may very well be what saves him. “The world ought to know what this Uyghur scholar has said,” Yaxue told me. “We want to advocate for his freedom. We have to persist until Ilham Tohti is free.”