Imagine that you’re movingthrough the world in a fog, able to control your body, but not feeling fully inside it — like you’re playing a video game of your life as a slightly removed spectator. This is how I experience my depersonalization-derealization disorder, a dissociative disorder that manifests as feeling disconnected from your body, mental processes, and surroundings.

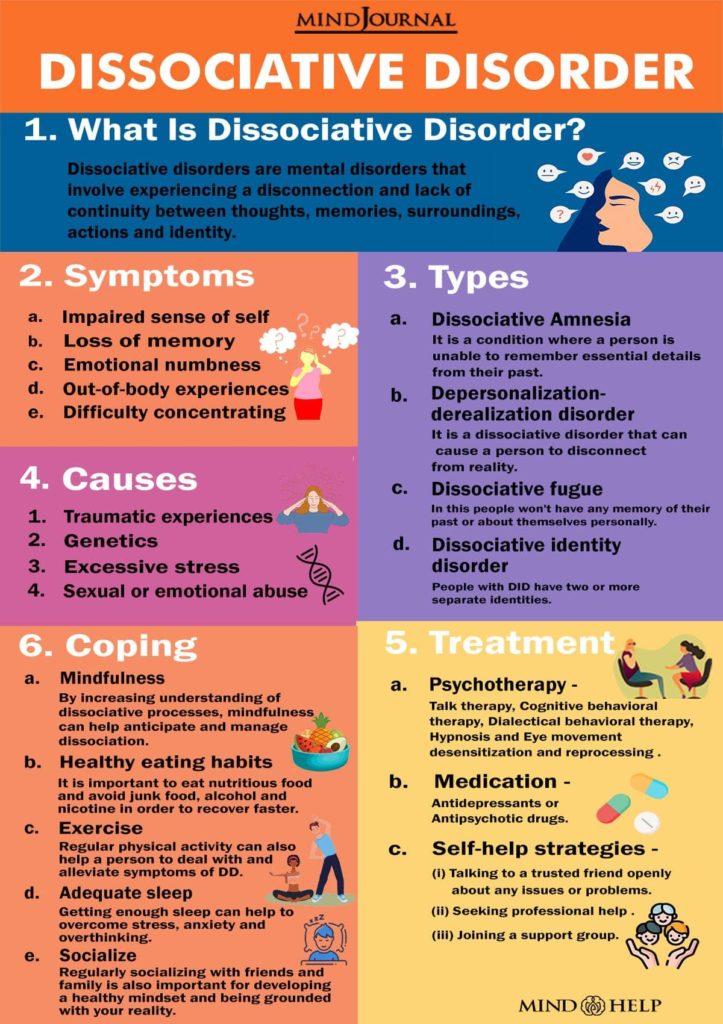

While dissociation equates to feeling detached, depersonalization is feeling distant from yourself; it’s like you are an outside observer of your body or acting as if on autopilot. Derealization means feeling removed from your environment, like you are living in a dream or a haze, or there’s an imaginary force field separating you from other people.

About half of all people experience these feelings at least once in their lifetime, but 2% meet the criteria for depersonalization-derealization disorder, and have repetitive and persistent episodes of dissociation.

I’ve noticed a growing tendency for people to mention dissociation on social media in a joking or casual manner, which is certainly a way to cope with not wanting to connect to the reality of the world. But these flippant references sometimes can feel like they’re betraying the severity of the condition. When it gets really bad, I shut down. I can’t speak to my loved ones or access my emotions. Sex is out of the question, because I feel like a shell of a human. There are monthlong stretches of my life where I question if I was ever really there at all.

“Dissociation is a normal and healthy response to trauma, stress, boredom, or overwhelm. It’s our brain giving us a break,” Andrea Gutiérrez-Glik, LCSW, told me. The level of dissociation can vary. To measure it, she applies the “back-of-the-head scale,” a tool that visualizes the extent of a person’s derealization via hand measurements. Holding your hand as far as you can from your face indicates that you’re feeling present. Holding it an inch closer to your face means, as Gutiérrez-Gilk put it, “I’m present, but maybe I’m thinking about what’s for dinner tonight.” Moving it a bit closer to your face, she said, might signify, “I’m not noticing how my body feels and I’m thinking about what I have to do later.” Placing your hand right up to your face means “you’re not aware of the present moment,” she said.