Hardly a night has passed in the last two months in which I’m not slowly backing away from someone in the music world talking to me about NFTs. Roughly one-third of them are espousing the digital tokens as a financial opportunity that’ll revolutionize their career, one-third of them disdainfully shout the words “shady” and “scammy,” and one-third are sheepishly asking me to explain to them what exactly NFTs are.

Until Monday night, though, I’d never heard an artist incorporating NFTs into their performance. Enter leopard print hairdo’d “CryptoPunk rapper” Spottie WiFi, to the stage at Empire Control Room.

“How many of y'all have that Chill Pill NFT? Don’t lie. It’s off the chain, bro,” Wifi polled the audience after his introductory song “I’m Spottie,” which contains references to the tech company Larva Labs, Top Shot NFT basketball cards, and POAPs, which are NFTs that prove your attendance at an event. Though Spottie WiFi famously sold $192,000 worth of music-related NFTs in 60 seconds, there would only be about 25 POAPs needed for his modestly attended SXSW showcase.

Is the awkward part over yet? I wonder in regard to music’s relationship with NFTs. Non-fungible tokens, digital assets containing unique codes that act as certificates of authenticity, have obvious societal uses but the implication that they’ll be a game-changing format for music still seems uncertain. In Austin’s music sphere, NFTs have suffered a rough emergence with the estate of late outsider-artist Daniel Johnston gaining heavy criticism and low bids for a Johnston NFT last April, the same month an arty token benefiting popular Austin venue the Mohawk sold for $20,000 less than its reserve bid. Then last month, there was an especially localized outcry against a website called HitPiece that listed NFTs of artist’s Spotify releases without their prior knowledge or permission. SXSW, where discussion and promotions of NFTs are widespread, arrives at a moment where concepts of digital music tokens have an opportunity to be both shamelessly shilled and boosted by professional endorsements and education.

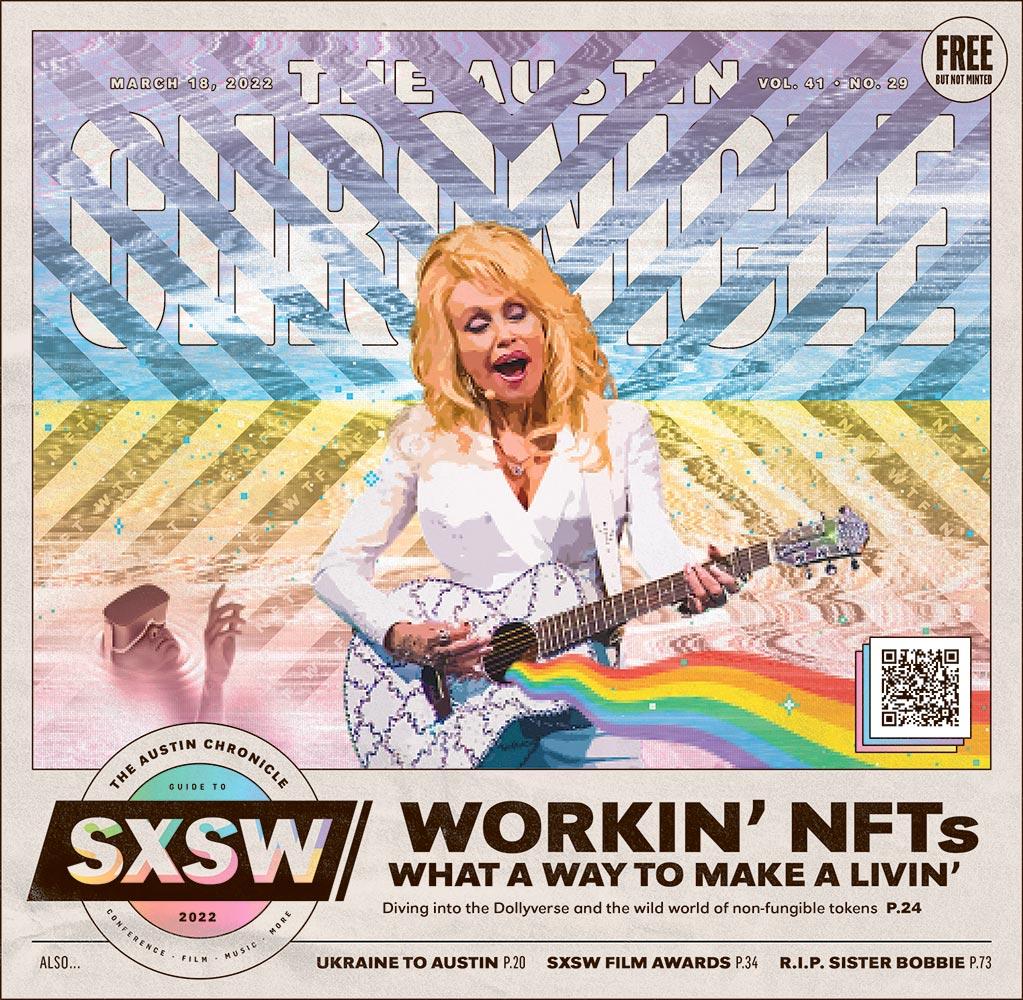

If one individual can bring dignity to a situation, it’s Dolly Parton. Thank Fox’s Blockchain Creative Labs for bringing the country music icon to Austin for her first SXSW appearance. In a press release, the universally loved 76-year-old characterized NFTs and SXSW as examples of her always wanting to try new things. Parton will perform at the Moody Theater on Friday night as part of an appearance with her James Patterson co-authored mystery novel Run, Rose, Run. Audience members will get an NFT commemorating the experience.

There have also been several panels seeking to elevate the conversations around music NFTs. On Saturday, I attended one at Blockchain Creative Labs’ installation titled “Can Blockchain Revolutionize Music Royalties?” which turned out to be more of a robust discussion about NFTs in terms of building fan communities, the decentralization of the online music industry, and what pitfalls artists should avoid when jumping into the NFT market.

Nait Jones, head of growth for the NFT distributor Royal, discussed a changing connection between musicians and listeners and what that means for the artist.

“There’s a shift in economic alignment between fans and artists. From my perspective, blockchain represents a way to organize communities and build economies on top of that,” he said. “With that, I feel like there’s going to be an explosion of new creativity as people are going to be able to actually work on their art all the time instead of doing other things – they can just work directly with their community.”

Also discussed: “value propositions,” or perks, that come with the minted digital product that NFT holders have bought. The British singer Kovic beamed about one such benefit.

“One of the things I did – totally spontaneously – was I just dropped a thing in an unlocked folder of my NFT and I was like, ‘I’m gonna fly anyone who holds all my NFTs to SXSW.’ I’ve got two people who I paid to fly in. The thing was how it made me feel, to be able to give these experiences.”

After a weekend in NFT land, I was struck by a few realizations. 1) As a fan, I don’t personally enjoy hearing musicians talk about art as an investment opportunity. 2) For all the talk of decentralizing, I don’t suspect working-class folks will own NFTs anytime soon. 3) While there’s good motivation to sell NFTs, not a single person in my life has expressed interest in owning one.

But now I’m actually the owner of two NFTs, which I keep in my SXSW Go app-connected wallet. One of them plays a song called “Solar Flare” by CatchTwentyTwo while I see a swirl of red and black goo. The other one is a WWE logo.

I don’t enjoy either of them at all, but I’m open to the possibility that I’ll one day have an NFT that I care about and, who knows, maybe it’s waiting for me in the “Dollyverse.” – Kevin Curtin

I didn’t have to go looking for NFT promotion at SXSW, because it was everywhere. The ease with which the form permeated the festival was absolutely stunning. Walking through Downtown during the tech-oriented first weekend, alphabet soup of the terms metaverse, Web3, and blockchain plastered poster after poster. The saturation surprised me.

Upon picking up my badge Saturday evening at the convention center, my more outgoing friend started talking to a writer with Vice’s Motherboard – the very kind Edward Ongweso – who was in town to host a panel on cryptocurrency skepticism. Hoping not to come off as total luddites with our own uninformed, jokey crypto uncertainty, we invited him to a nearby installation by Fox Entertainment-owned Blockchain Creative Labs – the festival’s first-ever blockchain sponsor, right up there with White Claw and the Chronicle on all the posters. Bachelor star Colton Underwood had been by earlier that day.

We were greeted by a docent in a white lab coat, who said, “Well, it’s a lab,” when asked about her attire. Scrolling text projected on the walls during the live-coded “algorave” DJ set, a concept I’d seen at SXSW 2019 and which isn’t particularly NFT-related but sure looks futuristic. After acquiring our free popcorn and ice cream tacos, Ongweso invited us to meet his friends on Rainey.

At a sectioned-off table at a bar taken over by CNN+, a very clean-looking man told me he was an Austin boy himself. He and his friend Jacob Silverman, a writer for The New Republic, were working on a book about crypto fraud. They’d already been by the projector-happy blockchain party, and celebrated getting a few leaders of decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs) – which the well-gelled man said weren’t actually decentralized or autonomous after all – to admit that they’d been scammed by crypto deals.

With disciples emphasizing the positive and hiding negative experiences, their thesis was: Crypto is a cult. Googling on our walk home, my friend and I identified our blond table mate as the actor Ben McKenzie, former star of The O.C. and host of a festival panel entitled “Trust Me I’m Famous: Ben McKenzie Questions Crypto.” He hoped to counterbalance celebrity-inspired FOMO over crypto moneymaking and ape NFTs.

Paris Hilton, after bragging about her own Bored Ape Yacht Club NFT on Jimmy Fallon, performd a local DJ set Wednesday night for an NFT gaming platform.

Celebrity, alongside free drinks and electronic music, proved essential in one of the first mainstream festival presentations of NFTs since the technology’s 2021 break. At home, I searched an inflatable geodesic dome we’d passed by at 4th and Red River, sponsored by bunny-pedaling NFT brand Fluf World, to find a livestream of Mike Shinoda from Linkin Park crafting a music NFT (aka a song) on a huge overhead screen. McKenzie’s cult accusations echoed in my head as I watched an Instagram story from inside the bubble.

A dramatic, disembodied masculine voice boomed: “This is changing the future. This is Fluf House. This is the Hume Collective, so remember why you are here. Remember the power that you have. The power of this community, and when it gets hard, remember you are not alone.”

Obviously pulling from the inspiration parlance of pop stars, the message also reminded me of corporate retreat scenes in documentaries about pyramid schemes. When I messaged the brand to inquire who was speaking, they wrote back, “Angelbaby, Fluf World’s first megastar.” He’s a pink 3D rabbit who premiered last year at Art Basel with Hume Collective, basically Fluf’s NFT-making version of a record label.

Over two days, the “Fluf Dome” also hosted sets by animate acts like Austin’s Ghostland Observatory and Ethereum-friendly Diplo collaborator Dillon Francis, who was asked by one fan to sign their carrot.

Stardom as an essential element to moneymaking metaverse moves continued Monday. A panel entitled “Move Over NFTs. Here Come the DAOs” focused on the latter as an investor-controlled alternative to a typical business or nonprofit. (Alex Zhang, introduced as the “de facto mayor” of The New York Times-featured crypto social club Friends With Benefits, explained DAOs as “basically a group chat with a shared bank account.”) When the moderator referred to panelist Nadya Tolokonnikova of Pussy Riot as a celebrity, she charmingly recoiled.

“No, celebrity is different,” she replied from behind a baseball cap, the morning after an intense performance at Cheer Up Charlies. Tolokonnikova focused on the upsides of crypto in launching UkraineDAO – which raised around $7 million for Ukrainian aid organizations – while allowing for quick distribution and anonymous donations from Russian citizens. Addressing the trivial reputation of NFTs, she described UkraineDAO as “a big step from crypto being perceived as just cartoon images that can be sold for more money than they’ve been bought.”

Elsewhere at SXSW, Tolokonnikova detailed Pussy Riot’s new UnicornDAO project, which will invest solely in female, nonbinary, and LGBTQIA artists. To her, the tech is just another tool in an ongoing search for better governance models.

“I refer to Pussy Riot as one of the first DAOs,” she said. “It’s basically the same thing, because it’s decentralized, it’s autonomous ... We always called for global solidarity and connection of activists. I mean [an] activist, in history, is just a person who is really, really bullish on a certain topic.” – Rachel Rascoe

Festivalgoers take in the sights at SXSW's NFT gallery (Photo by David Brendan Hall)In the year 2022, most musicians don’t earn money selling their music. I know, because I’m one of them.

Last year I released an EP on Bandcamp and Spotify. My music partner and I probably spent 100 hours working on the project and grossed about 10 bucks in MP3 sales.

It may sound like I’m playing a synthesizer programmed to sound like the world’s tiniest violin, but I’m not begging for sympathy – I’m just asking not to be made fun of for trying to find a way to get paid for my work.

On a surface level, it’s reasonable to despise NFTs. There’s nothing easier to hate than new money, and crypto bros spending millions on pixelated art fall firmly in this category. It’s confusing that someone would invest in a digital image which can be enjoyed online for free.

Same thing goes for an MP3. It isn’t an asset, because it can be copied infinitely. Turn that MP3 into a physical object and you have something with rarity, a collectible accompanied by visual art and liner notes. Maybe there’s even a splatter of bright colors on the vinyl itself, a hypnotizing visual to spin on your turntable. If the record sells out, demand and price will rise. Hell, 30 years later someone might pay $1,000 for that first pressing ... even though you could just stream it off YouTube.

Scarcity is the reason record collectors pay handsomely for rare albums, and digital music lacks scarcity. Now imagine if those same components that make a record appealing could be applied to an MP3. Add in a cool looping video and bonuses like audio stems. Then there’s an element of collectibility that has the potential to appeal to record collectors.

That’s why I’m excited about the potential that NFTs offer musicians, and why I’m brushing up on my Photoshop skills and learning video animation. An NFT is just a multimedia item that a musician can add to their merch table.

Of course, the digital music files can still be copied, just as a rare record can be streamed. But think of the blockchain – where these NFTs are essentially pressed – as wet digital concrete. When you mint an NFT, you’re writing in that concrete. The person who buys the NFT owns that strip of sidewalk, and can resell it later.

All that said, you may think to yourself, “This guy is crazy, I’m never gonna buy an NFT.” But here’s the thing: I’m not expecting you to. At least not yet.

I don’t think the average music listener will browse OpenSea to drop hundreds of dollars on music NFTs anytime soon. Right now, most music NFT owners aren’t doing so out of practical use, but rather out of patronage (side note, think of an NFT as a Patreon membership that you can resell). The wealthy have always subsidized the arts. And on the digital frontier, those patrons aren’t oil families, they’re people who bought bitcoin in 2015. The same crypto bros trading million-dollar JPEGs listen to music, too.

Right now, this Web3 stuff is the equivalent of the 1995 era of the internet, a Wild West of scams and technogarble and Pets.com stocks. It made sense then that my dad was hesitant to put his credit card number into an America Online website, and it makes sense to be wary of installing a cryptocurrency wallet web extension now. But today, even my dad knows how to stream to music online, and he also understands that musicians aren’t the ones profiting.

It’s universally agreed upon that the current music streaming landscape is fundamentally broken. We’re all essentially renting access to songs on Spotify, paying a slumlord who won’t provide heat for working musicians. Is it so crazy to think that a few years from now, selling NFTs might just be a way for musicians to keep the lights on? – Dan Gentile